Them

by Mike Resnick

Carol has a high threshold for embarrassment. You can’t be married to me for 42 years and not have one. But recently she has announced that she will no longer sit next to me at science fiction movies, that indeed she will sit on the far side of the theater and do her very best to pretend that she doesn’t know me.

She’s right. I’m just not much fun to be around at science fiction movies. I don’t know quite how this came about. I used to love them when I was growing up. I forgave them their lack of special effects and their B-movie casts and budgets. OK, so Them paid no attention to the square-cube law; except for that, it was as well-handled as one could possibly want. And maybe The Thing wasn’t quite what John Campbell had in mind when he wrote “Who Goes There?”, but it was treated like science fiction rather than horror (the same cannot be said for the big-budget remake), and the overall ambience was rational. As for Forbidden Planet, nothing I’ve seen in the last 50 years has stirred my sense of wonder quite as much as Walter Pidgeon’s guided tour of the wonders of the Krell. A decade and a half later Stanley Kubrick made a trio of wildly differing but excellent science fiction movies—Dr. Strangelove, 2001: A Space Odyssey, and A Clockwork Orange—each of which treated the field with respect.

Then, just about the time I became a full-time science fiction writer, Hollywood started turning out one intellectually insulting science fiction movie after another. I mean, these things were almost dumber than network television shows. And I started muttering—louder and louder with each movie, Carol assures me—things like “No editor paying 3 cents a word for the most debased science fiction magazine in the world would let me get away with that!” Before long audiences would pay more attention to my rantings than to the movies.

I keep hearing that science fiction movies are getting better, that once George Lucas showed what could be done on the big screen we no longer have anything to be ashamed of when comparing ourselves to other genres.

That makes me mutter even louder.

So let me get it off my chest, which is a figure of speech, because actually the stupidity of science fiction movies is much more likely to eat a hole in my stomach lining.

And let me add a pair of stipulations:

First, I’m only interested in movies that aspired to be arch-bishop, which is to say, movies with major budgets and major talent that really and truly meant to be good movies. I will not consider such epics as Space Sluts in the Slammer (yes, it really exists), as it seems not unreasonable to assume it was never meant to be a contender for the year-end awards.

Second, when I speak of stupidities, I’m not talking about the nit-picking that goes on in outraged letter columns. If the math or science are wrong only in areas that scientists, mathematicians, or obsessive science fiction fans would find fault with, I’ll ignore it. If George Lucas doesn’t know what a parsec is, or Gene Roddenberry and his successors think you can hear a ship whiz by in space, I’m willing to forgive and forget.

So what’s left?

Well, let’s start with Star Wars. First, has no one except me noticed that it’s not pro-democracy but pro-royalty? I mean, all this fighting to depose the Emperor isn’t done to give the man on the street (or the planet) a vote; it’s to put Princess Leia on the throne and let her rule the galaxy instead of him, which is an improvement only in matter of degree. And it drives me crazy that in 1991 we could put a smart bomb down a chimney, and that in 2002 we could hit a target at 450 miles, but that computerized handguns and other weaponry can’t hit a Skywalker or a Solo at 25 paces.

Return of the Jedi? Doesn’t it bother anyone else that Adolf Hitler—excuse me; Darth Vader—the slaughterer of a couple of hundred million innocent men and women, becomes a Good Guy solely because he’s Luke’s father?

Return of the Jedi? Doesn’t it bother anyone else that Adolf Hitler—excuse me; Darth Vader—the slaughterer of a couple of hundred million innocent men and women, becomes a Good Guy solely because he’s Luke’s father?

And what could be sillier than that final scene, where Luke looks up and sees Yoda and the shades of Darth Vader and Obiwan Kenobi smiling at him. That was too much even for Carol, whose first comment on leaving the theater was, “Poor Luke! Wherever he goes from now on, he’s a table for four.”

Then along came E.T., which, for a few years at least, was the highest-grossing film of all time, until replaced by an even dumber one.

You think it wasn’t that intellectually insulting? Let’s consider the plot of that billion-dollar grosser, shall we?

1. If E.T. can fly/teleport, why doesn’t he do so at the beginning of the film, when he’s about to be left behind? (Answer: because this is what James Blish used to call an idiot plot, which is to say if everyone doesn’t act like an idiot you’ve got no story.)

2. What mother of teenaged children walks through a kitchen littered with empty beer cans and doesn’t notice them? (Answer: in all the world, probably only this one.) This is the blunder that started me muttering loud enough to disturb other moviegoers for the first time.

3. While we’re on the subject of the mother and the kitchen, what is a woman with an unexceptional day job doing living in an $900,000 house in one of the posher parts of the Los Angeles area? (Even I don’t have an answer to that.)

4. Why does E.T. die? (Answer: so he can come back to life.

5. Why does E.T. un-die? (Still awaiting an answer, even a silly one, for this.)

6. When E.T. finally calls home, the lights in the room don’t even flicker. I’m no scientist, but I’d have figured the power required would have shorted out the whole city.

Cheap shots, Resnick (I hear you say); you’re purposely avoiding the films that were aimed at an adult audience, films like Blade Runner and Signs, for example.

All right. Let’s take Blade Runner (and someone please explain the title, since I never saw a blade or a runner in the whole damned movie). Great future Los Angeles; it really put you there. Nice enough acting jobs, even if Harrison Ford was a little wooden. Wonderful sets, costumes, effects.

But the premise is dumber than dirt. We are told up front that the androids are going to expire in two weeks—so why in the world is Harrison Ford risking his life to hunt them down when he could just go fishing for 14 days and then pick up their lifeless bodies?

But that premise looks positively brilliant compared to the critically-acclaimed Mel Gibson movie Signs, which grossed about half a billion dollars worldwide two short years ago.

Consider: would you travel 50 trillion miles or so for a little snack? That’s what the aliens did. If they’re here for any other reason except to eat people, the film never says so.

OK, let’s leave aside how much they’re paying in terms of time and energy to come all this way just to eat us for lunch. What is the one thing we know will kill them? Water (which also killed the Wicked Witch of the West, a comparison that was not lost on some perceptive viewers). And what are human beings composed of? More than 90% water.

So the aliens come all this way to poison themselves (and then forget to die until someone hits them with a baseball bat, which Hollywood thinks is almost as devastating a weapon against aliens of indeterminate physical abilities as a light-sabre.)

By now I didn’t just mutter in the theater, I yelled at the screenwriters (who, being 3000 miles away, probably didn’t hear me.) But I figured my vocalizing would soon come to an end. After all, we all knew that the sequel to The Matrix would show the world what real science fiction was like; it was the most awaited movie since Lucas’ all-but-unwatchable sequels to the original Star Wars trilogy.

By now I didn’t just mutter in the theater, I yelled at the screenwriters (who, being 3000 miles away, probably didn’t hear me.) But I figured my vocalizing would soon come to an end. After all, we all knew that the sequel to The Matrix would show the world what real science fiction was like; it was the most awaited movie since Lucas’ all-but-unwatchable sequels to the original Star Wars trilogy.

So along comes The Matrix Retarded . . . uh, sorry, make that Reloaded. You’ve got this hero, Neo, with godlike powers. He can fly as fast and far as Superman. He can stop a hail of bullets or even bombs in mid-flight just by holding up his hand. He’s really remarkable, even if he never changes expression.

So does he fly out of harm’s way when a hundred Agent Smiths attack him? Of course not. Does he hold up his hand and freeze them in mid-charge? Of course not. Can Neo be hurt? No. Can Agent Smith be hurt? No. So why do they constantly indulge in all these easily avoidable, redundant, and incredibly stoopid fights?

Later the creator of the Matrix explains that the first Matrix was perfect. It only had three or four flaws, which is why he built five more versions of it. Uh . . . excuse me, but that’s not that way my dictionary defines “perfect.”

You want more foolishness? The whole world runs on computers, which means the whole world is powered by electricity to a far greater extent than America is at this moment. So why is the underground city lit only by burning torches?

I hit J above high C explaining to the screen what the least competent science fiction editor in the world would say to the writer who tried to pawn The Matrix Reloaded off on him.

Now, you’d figure Stephen Spielberg could make a good science fiction movie, wouldn’t you? I mean, he’s the most powerful director in Hollywood’s history. Surely if he wanted to spend a few million dollars correcting flaws in the film before releasing it to the public, no one would dare say him nay.

So he makes Minority Report, and to insure the box office receipts he gets Tom Cruise to star in it and announces that it’s based on a Philip K. Dick story. (Dick is currently Hollywood’s favorite flavor of “sci-fi” writer, this in spite of the fact that nothing adapted from his work bears more than a passing resemblance to it.)

And what do we get for all this clout?

Well, for starters, we get a future less than half a century from now in which the Supreme Court has no objection to throwing people in jail for planning crimes.

We get a scene where Tom Cruise escapes from the authorities by climbing into a car that’s coming off an assembly line and driving off in it. That one really got me muttering at a hundred-decibel level. Has anyone ever seen a car come off an assembly line with a full tank of gas?

We are told that the three seers/mutants/whatever-they-are can only foresee capital crimes. Even bank robberies slip beneath their psychic radar. But in a crucial scene, one of them predicts a necessary rainstorm. (I hit 120 decibels on that one.)

It’s also explained that they have physical limits. If they’re in Washington, D.C., they can’t foresee a crime in, say, Wilmington, Delaware. But the villain of the piece, who knows their abilities and limitations better than anyone, plans to use them to control the entire nation, which the last time I looked at a map extends even beyond Delaware. (140 decibels that time.)

OK, I’m too serious. These are just entertainments. I should go see one made from a comic book—Hollywood’s intellectual Source Material Of Choice these days—and just sit back and enjoy it.

Good advice. So we went to see Hulk. You all know the story; it’s swiped from enough science fictional sources. I didn’t mind the poor animation. I didn’t mind the idiot plot that had Bruce Banner’s father responsible for his affliction. I didn’t mind this; I didn’t mind that. Then we came to Thunderbolt Ross, the 5-star general—and suddenly I was muttering again.

I was willing suspend my disbelief for this idiocy, but alas, I couldn’t suspend my common sense. Here’s this top military commander, the film’s equivalent of Norman Shwartzkopf or Tommy Franks. And here’s the Hulk, who makes Superman look like a wimp. Now, you have to figure that even a moderately bright 6-year-old ought to be able to conclude that if attacking the Hulk and shooting him doesn’t hurt him, but just makes him bigger and stronger and angrier and more destructive, the very last thing you want to do when he’s busy being the Hulk rather than Bruce Banner is shoot or otherwise annoy him, rather than simply wait for him to change back into his relatively helpless human form. That, however, seems to be beyond both our general and our screenwriters.

Even the good science fiction movies assume that their audiences are so dumb that logic means nothing to them, as long as you dazzle them with action and zap guns and aliens and the like.

Take The Road Warrior (a/k/a Mad Max 2), which is truly a fine movie: well-acted, well-conceived, well-directed. And yet . . .

Take The Road Warrior (a/k/a Mad Max 2), which is truly a fine movie: well-acted, well-conceived, well-directed. And yet . . .

In The Road Warrior’s post-nuclear-war future, the rarest and most valuable commodity in the world is refined oil (i.e., gasoline), because the distances in Australia, where it takes place, are immense, and you can’t get around without a car or a motorcycle. The conflict takes place between the Good Guys, who have built a primitive fortress around a refining plant, and the Bad Guys, a bunch of futuristic bikers, who want to get their hands on that gasoline, which is so rare that it’s probably worth more per drop than water in the desert.

So what do the bad guys who desperately need this petrol do? They power up their cars and bikes and race around the refinery for hours on end, day in and day out. If they would have the brains to conserve a little of that wasted energy, they wouldn’t have to risk their lives trying to replace it. (And, while I’m thinking of it, where do they get the fuel to power their dozens of constantly-running vehicles?)

Then there were Spielberg’s mega-grossing dinosaur movies, Jurassic Park and The Lost World. The former hypothesizes that if you stand perfectly still six inches from a hungry Tyrannosaurus Rex he won’t be able to tell you’re there. I would like to see the screenwriter try that stunt with any hungry carnivore—mammal or reptile—that has ever lived on this planet. The latter film shows you in graphic detail (and with questionable intelligence) that a T. Rex can outrun an elevated train, but cannot catch a bunch of panicky Japanese tourists who are running away, on foot, in a straight line.

Although these two films are the prime offenders, simply because Spielberg has the resources to know better, I am deathly tired of the superhuman (uh . . . make that supercarnosaur) feats with which Hollywood endows T. Rex, who seems to be the only terrifying dinosaur of which it was aware until someone told Spielberg about velociraptors. (Give them another decade or two and they might actually discover allosaurs and Utahraptors.)

T. Rex weighed about seven tons. By comparison, a large African bull elephant weighs about six tons, and could probably give old T. Rex one hell of a battle. But no one suggests that a six-ton elephant can throw trucks and trains around, break down concrete walls, or do any of the other patently ridiculous things T. Rex can do on screen.

And the list—and the intellectually offended muttering— goes on and on. In Alien they all go off by themselves to search for the creature; haven’t they learned anything from five centuries of dumb horror movies? At the end of Total Recall, Governor Schwarzenegger is outside for maybe six minutes while Mars is being miraculously terraformed. Just how long do you think you could survive on the surface of Mars in 100-below-zero weather with absolutely no oxygen to breathe?

Some “major” films are simply beneath contempt. I persist in thinking that Starship Troopers was misnamed; it should have been Ken and Barbie Go To War. And if that wasn’t a bad enough trick to pull on Robert A. Heinlein after he was dead, they also made The Puppet Masters, which was handled exactly like a 4th remake of Invasion of the Body Snatchers.

Then there’s Armageddon, which seems to make the case that it’s easier to teach hard-drinking functionally illiterate wildcatters how to be astronauts in a constricted time period than to teach highly intelligent physically fit astronauts how to drill for oil. And Ghod help us, it was Disney’s highest-grossing live action film until Pirates of the Caribbean came along.

And when I was sure it couldn’t get any worse, along came the stupidest big-budget film of all time—The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen.

Consider:

1. Allan Quatermain can hit a moving target at 900 yards in the year 1899 A.D. With a rifle of that era.

2. Bruce Banner—excuse me: Dr. Jeckyl—changes into the Hulk—oops: make that Mr. Hyde—and suddenly he’s 15 feet tall and even his muscles have muscles. He’s a bad guy—except when, at the end, the plot requires him to be a good guy and rescue all the other good guys at enormous personal cost, which he does for no rational reason that I could discern.

3. Mina Harker is a vampire. She’s Jonathan Harker’s wife, and Jonathan, as you’ll remember, is the guy who visits Dracula and sells him an English estate. (I always felt Dracula shouldn’t have stopped terrifying realtors with just one, but let it pass.) Well, Mina is a Good Guy, and certainly, given her physical features, a more Extraordinary Gentleman than any of the others. She can fly (Dracula couldn’t), she can cross over water (movie vampires can’t), and she can command a combat team (honest) of half a million bats. She also drinks blood, but only of Bad Guys.

4. The Invisible Man joins the team. Well, no one reads H. G. Wells any more, so they announced that the original Invisible Man was dead and this cockney guy has replaced him. He spends most of his time being invisible in sub-zero weather, occasionally mentioning that it’s chilly without his clothes on, but he never gets dressed or goes inside.

5. Dorian Gray. Well, he’s got this picture, see? Oh, and he can’t be harmed. Cut him, shoot him, and two seconds later he’s whole, unharmed and unmarked. But if he should ever see his picture, he turns immediately and gruesomely and eternally to dust. Funniest action scene in the picture is a fight to the death (honest!) between Dorian Gray, who literally cannot be harmed or killed, and Mina Harker, who is already dead.

6. Captain Nemo is a bearded Indian who is a master of karate.

7. The only Victorian figure missing is Sherlock Holmes, so of course the youngish villain turns out to be Moriarty (who Sherlock killed when he was an aging professor a few years before 1899.)

8. And, oh yeah, there’s an American secret agent named Tom Sawyer, who’s about 22 years old—a really neat trick since he was a teenager before the Civil War.

I think it’s nice that the screenwriter brought back all these Victorian and pre-Victorian characters. It would have been even nicer if he’d ever read a single book in which they appeared.

How do they travel? In a half-mile-long 20-foot-wide version of the Nautilus. (And as this 2500-foot-long ship is going through the canals of Venice, even Carol couldn’t help wondering how it turned the corners.)

There is a convertible car. (After all, this is 1899. They hadn’t invented hardtops yet.) Allan Quatermain and two other Extraordinary Gentlemen have to drive down the broad paved boulevards (broad paved boulevards???) of Venice. There are 200 Bad Guys on the roofs on both sides of the street, all armed with automatic weapons. They fire 18,342 shots at the car—and miss. Allan Quartermain and his ancient rifle don’t miss a target for the entire and seemingly endless duration of the film.

What are the Extraordinary Gentlemen doing? They’re stopping Moriarty from getting rich by selling weapons to rival European nations. And where is he getting these weapons? Easy. He has built a two-mile-square fortified brick city/fortress in the middle of an ice-covered Asian mountain range, and filled it with thousands of machines capable of creating really nasty weapons. I figure the cost of creating the city, shipping in the tons of iron he has to melt to make weapons, and building/importing the thousands of machines required to build the weapons, set him back about $17 trillion. But he’s going to make $200 million or so selling weapons, so he’s in profit. Isn’t he???

Every single aspect of the film is on this level. Nairobi consisted of two—count them: two—tin-roofed shacks in 1899, but in the movie it’s a city. And it’s a city in clear sight of Kilimanjaro—which is passing strange, because every time I’ve been there it’s a 2-hour drive just to see Kilimanjaro in the distance. Quatermain lives in a place which I suppose is meant to be the Norfolk Hotel, but looks exactly like an anti-Bellum Southern mansion, complete with liveried black servants who speak better English than Sean Connery (who plays Quatermain and will be decades living it down).

It’s mentioned a few times that Allan Quatermain can’t die, that a witch doctor has promised him eternal life. In the end he dies, and despite his having repeated this story about the witch doctor ad nauseum, the remaining Extraordinary Gentlefolk take his body—unembalmed, I presume—all the way from the Asian mountains to East Africa and bury him there, place his rifle on the grave, and walk away. Then the witch doctor shows up, does a little buck-and-wing and a little scat-singing, and the rifle starts shaking as if something’s trying to get out of the grave. End of film. My only thought was: “It’s the writer, and they didn’t bury him deep enough.”

OK, I’ve really got to calm down. I’m starting to hyperventilate as I write this.

(Pause. Take a deep breath. Think of flowers swaying in a gentle breeze. Pretend they are not about to be trampled by a 45-ton Tyrannosaur that has just eaten a homo erectus that looks exactly like Raquel Welch, make-up and wonder bra included. Return to keyboard.)

I prefer science fiction to fantasy both as a writer and a reader. I prefer the art of the possible to the impossible, the story that obeys the rules of the universe (as we currently know them, anyway) to the story that purposely breaks them all. And yet . . . and yet, for some reason that eludes me, Hollywood, which seems unable to make a good science fiction movie to save its soul (always assuming it has one, an assumption based on absolutely no empirical evidence), has made a number of wonderful fantasy movies that are not intellectually offensive and do not cheat on their internal logic: Field of Dreams, Harvey, The Wonderful Ice Cream Suit, The Devil and Daniel Webster, Portrait of Jennie, even The Wizard of Oz and the Harry Potter films (well, the first one, anyway).

No, this is not blanket praise for all fantasy films. As I was walking out of The Two Towers I complained to Carol that I’d just wasted three hours watching what amounted to spring training for the real war in the next film. And about three hours into The Return of the King, as I was watching the 20th or 25th generic battle between faceless armies that I didn’t care about, I had this almost-unbearable urge to find an usher and say, “Let my people go!”

No, this is not blanket praise for all fantasy films. As I was walking out of The Two Towers I complained to Carol that I’d just wasted three hours watching what amounted to spring training for the real war in the next film. And about three hours into The Return of the King, as I was watching the 20th or 25th generic battle between faceless armies that I didn’t care about, I had this almost-unbearable urge to find an usher and say, “Let my people go!”

But for the most part, I find that fantasy movies don’t raise my bile the way science fiction movies do. How can big-budget science fiction films be so ambitious and so dumb at the same time, so filled with errors that no editor I’ve ever encountered (and that’s a lot of editors, including some incredibly lax ones) would let me get away with?

Uh . . . Carol just stopped by. She said she heard me muttering and cursing and wondered what the problem was. I invited her to read a bit of this article over my shoulder.

*Sigh* Now she says she won’t sit in the same room with me when I’m writing about science fiction movies.

Elwood P. Dowd and Harvey

©Mike Resnick 2009

Originally Appeared in Challenger #12

Mike on a panel at WorldCon Denver 2008

Mike with Champions The Gray Lensman and Silverlock

Read Full Post »

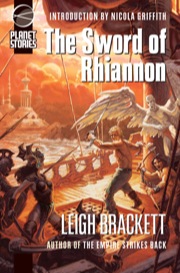

The Reavers of Skaith, by Leigh Brackett, is the final novel in the saga of Eric John Stark, Brackett’s most beloved SF character. It’s the fourth of the five Brackett books Planet Stories has published to date, with a stunning cover by James Ryman and an introduction by film director George Lucas, who discusses Brackett’s role in writing the first draft of The Empire Strikes Back and her influence upon the entire Star Wars saga. We were blown away that Lucas was able and willing to write such a thoughtful introduction for us, and this book looked like it had everything going for it and would become one of our strongest sellers.

The Reavers of Skaith, by Leigh Brackett, is the final novel in the saga of Eric John Stark, Brackett’s most beloved SF character. It’s the fourth of the five Brackett books Planet Stories has published to date, with a stunning cover by James Ryman and an introduction by film director George Lucas, who discusses Brackett’s role in writing the first draft of The Empire Strikes Back and her influence upon the entire Star Wars saga. We were blown away that Lucas was able and willing to write such a thoughtful introduction for us, and this book looked like it had everything going for it and would become one of our strongest sellers.

Author and noted sf critic Paul Kincaid has just posted

Author and noted sf critic Paul Kincaid has just posted

Leigh Brackett wrote the first draft of The Empire Strikes Back and worked with William Faulkner on The Big Sleep, but her greatest contribution to science fiction was a series of tales set on a fantastic Mars. Brackett’s Red Planet was a place of ancient cities perched on the crumbling cliffs of dry canals and the windswept seabeds of ancient oceans, a world of adventurers and confidence men and swordsmen and thieves. The latest Planet Stories release,

Leigh Brackett wrote the first draft of The Empire Strikes Back and worked with William Faulkner on The Big Sleep, but her greatest contribution to science fiction was a series of tales set on a fantastic Mars. Brackett’s Red Planet was a place of ancient cities perched on the crumbling cliffs of dry canals and the windswept seabeds of ancient oceans, a world of adventurers and confidence men and swordsmen and thieves. The latest Planet Stories release,

By now I didn’t just mutter in the theater, I yelled at the screenwriters (who, being 3000 miles away, probably didn’t hear me.) But I figured my vocalizing would soon come to an end. After all, we all knew that the sequel to The Matrix would show the world what real science fiction was like; it was the most awaited movie since Lucas’ all-but-unwatchable sequels to the original Star Wars trilogy.

By now I didn’t just mutter in the theater, I yelled at the screenwriters (who, being 3000 miles away, probably didn’t hear me.) But I figured my vocalizing would soon come to an end. After all, we all knew that the sequel to The Matrix would show the world what real science fiction was like; it was the most awaited movie since Lucas’ all-but-unwatchable sequels to the original Star Wars trilogy. Take The Road Warrior (a/k/a Mad Max 2), which is truly a fine movie: well-acted, well-conceived, well-directed. And yet . . .

Take The Road Warrior (a/k/a Mad Max 2), which is truly a fine movie: well-acted, well-conceived, well-directed. And yet . . .

No, this is not blanket praise for all fantasy films. As I was walking out of The Two Towers I complained to Carol that I’d just wasted three hours watching what amounted to spring training for the real war in the next film. And about three hours into The Return of the King, as I was watching the 20th or 25th generic battle between faceless armies that I didn’t care about, I had this almost-unbearable urge to find an usher and say, “Let my people go!”

No, this is not blanket praise for all fantasy films. As I was walking out of The Two Towers I complained to Carol that I’d just wasted three hours watching what amounted to spring training for the real war in the next film. And about three hours into The Return of the King, as I was watching the 20th or 25th generic battle between faceless armies that I didn’t care about, I had this almost-unbearable urge to find an usher and say, “Let my people go!”